It is no exaggeration to say that Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is a foundational text to the Size fetish. Due to its renowned literary and satirical merit and prolific public domain adaptations, people for centuries have been exposed to its whimsical vocabulary and striking imagery. Swift’s use of corporeal humor is memorably central to the narrative, making the contemplation of Sizey sexytimes unavoidable.

I am continually alert to mentions of Gulliver’s Travels in any context, from pop culture to academic inquiry, hoping to find digressions into or even explorations of the ribald possibilities presented by the plot. The results are usually disappointing, and I often find myself extrapolating furiously from a single phrase to identify the slightest indication that the author regarded the notion of Sizey sex as anything other than dry social commentary or a sight gag.

It was on one such mission that I discovered “The Sexual Politics of Microscopy in Brobdingnag,” a 2007 article in the academic journal Studies in English Literature. The article is a rigorous discussion of how “A Voyage to Brobdingnag” reflects the sociological impact of the rise of female-centered consumer culture in 18th-century England as it encountered the availability of cheap and accessible microscopes to the greater public.

I noted with interest that the author was female: Deborah Needleman Armintor. It remains the case in our society that women are more reserved than men are when it comes to remarking on paraphilic implications, and I am always seeking evidence that Size fetishes are not a male-only enthusiasm. I was pleasantly surprised to see that Armintor not only discusses at length the grotesquely detailed observations afforded to Gulliver by his close proximity to the giant bodies of Brobdingnagian women, she also rebuts the conventional analysis of those passages as evidence of Swift’s misogyny.

Most notably, Armintor makes explicit the precise activity for which the Brobdingnagian maids of honour covet the dildo-sized Gulliver. She compellingly links Gulliver’s reticence to detail being vaginally consumed to social anxiety at Englishwomen exercising their new power as commercial consumers. Gulliver’s expressions of disgust, therefore, should not be interpreted as misogyny but rather as Swift’s mockery of anxious English masculinity. I also quite appreciated Armintor characterizing the maids’ of honour desire to use Gulliver as a dildo as a perfectly natural female appetite and not as a deviant practice of an exotic foreign culture.

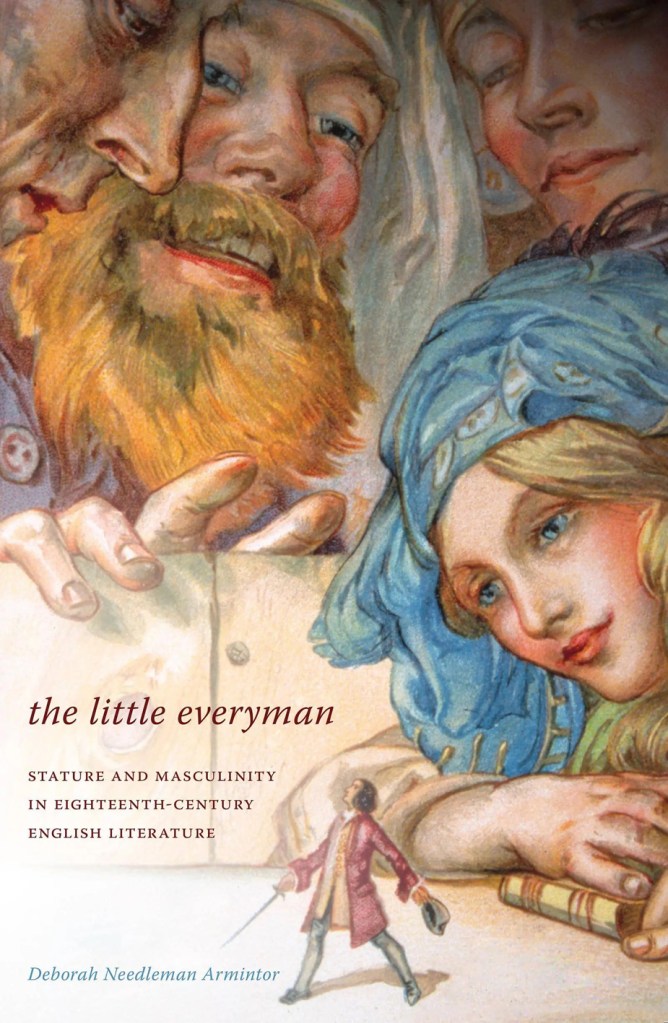

Some years later a fellow Size scholar alerted us to the fact that that Armintor had expanded this article into a book, The Little Everyman: Stature and Masculinity in Eighteenth-Century English Literature. The microscopy/Brobdingnag article was fleshed out into one chapter of six covering the image and role of “the little man” in English culture as the nation moved from an aristocrat-centered society to one focused on the emerging bourgeoisie.

Armintor begins her survey with royal portraits that include court dwarfs, whose images shift from monstrosity and mockery to spectator and stand-in. The second chapter deals with that “dwarf of letters,” Alexander Pope, and how his shortness informed both his writing and his celebrity. Tellingly, the relation that most emphasizes these dwarfs’ roles is that with “normal size women.” Court dwarfs “enjoy” being seen as nonthreatening to noble ladies while cultivating the myth of sexual prowess developed as “compensation” for their slight stature.

For many years I have had a vague notion that Henry Fielding’s Tom Thumb contained bawdy innuendo regarding the eponymous character’s relations with the ladies of King Arthur’s court. Armintor explicates this, continuing to extol the conjugal charms of a thumb-sized husband. Here, the socio-historical change is in the view of marriage from one of a property transaction between father and husband to one of “companionate marriage” where female preferences and desire play a greater role. Fielding also wrote a series of poems to his future wife, including “On Her Wishing to Have a Lilliputian to Play With,” which prioritizes the sensual pleasure of a normal size woman in possession of a penis-sized man at the expense of his own capacity for gratification. He must then take solace in his ability to delight her.

Armintor concludes the book with discussions of three other notable short men in 18th-century England, Christopher Smart, William Hay, and Josef Boruwlaski, and their struggles to find dignified relations with normal size women in a society that is starting to demand that men express a deeper sentimentality. Each of these little men attempt to demonstrate that their small size is offset by their large hearts, but they all eventually have to admit failure.

I am fascinated by Armintor’s choice to evaluate “stature and masculinity” primarily through the lens of little men’s capacity to please and satisfy normal size women. From the adolescent beginnings of my shrunken man fantasies I have clung to the conceit that a mouse-sized man would be uniquely attractive to women for both his lack of physical threat and his ability to provide selfless and finely-detailed attention toward her gratification. Other academic discussions of Gulliver’s Travels have touched on this theme, but Armintor dives straight into it.

Owing to the scholarly nature of her inquiry, Armintor restricts the scope of The Little Everyman to 18th-century England, but it is quite easy for this Size historian to imagine her continuing her analysis through history up to the present day. Her survey of the shifting nature of courtship and marriage would undoubtedly find its zenith in Charles Dana Gibson’s famous illustration, “The Weaker Sex II.” I would also like to see Armintor catalog all the reviews, adaptations, pastiches, homages, and parodies of Gulliver’s encounters with the Brobdingnagian maids of honour. It beggars the imagination that she might be unfamiliar with Judith Johnson Sherwin’s “Voyages of a Mile-High Fille de Joie.”

The Little Everyman is filled with descriptions of women taking delight in little men, not only as dildos but also as pocket poets, kept pets, and animate dolls. The feminine rush to handle and manipulate a little man is presumed to be instinctive and universal. That a woman authored this study invites speculation as to her own Sizey predilections.

For someone seeking validation for the popularity of a Size fetish—at least one of the F/m variety—The Little Everyman has a lot to offer. In addition to the plentiful excerpts and explicit interpretations there are thorough end notes and a rich bibliography. I naively hope that the next filmmaker to adapt Gulliver’s Travels is exposed to this book.

Thank you. Could you please write about Leroy Yerxa’s “Cosmic Sisters” of Astounding Sept 1946 as a precursor for Arthur C Clarke’s “Cosmic Casanova”.

Also consider “Asimov’s Annotated” and Hungarian film “Az Oriasok Orszagaban”(1982) starring Agi Szirtes & Andrea Drahota where they show “Brobdingnagian Maids of Honor at their Dressing table of toiletries” for a gender role reversal.

Remember Franchoise Boucher painting of how a lady used a gravy boat “bourdaloue” to urinate of how dirty unclean people where before plumbing.

LikeLike

“The History of Fashion” an extra in of “Barnes & Noble” describes a chapter on how dressing table of toiletries used by 18th Century royal maids would have used a “Powder machine” of a “bellows like device” as a forerunner of aerosol atomizer sprays.

Rember how Swift’s protagonist described how they layered over their acne with perfumes similar to a rainstorm’s nimbus clouds to consider how Steinmetz of 1917 & Keitaro Yoshihara had patented weather modification able to duplicate precipitation storms.

LikeLike